Two Types of Thinking

Soldier Mindset

Reasoning is like defensive combat. Finding out you’re wrong means suffering a defeat. Seeks out evidence to fortify and defend your beliefs.

Directionally motivated reasoning. When we want something to be true, we ask, “Can I believe this?” When we don’t want something to be true, we ask, “Must I believe this?”

Scout Mindset

Reasoning is like mapmaking. Finding out you’re wrong means revising your map. Seeks out evidence that will make your map more accurate.

Accuracy motivated reasoning evaluates the ideas through the lens of “Is it true?”

What the Soldier Mindset is Protecting

The Soldier Mindset helps us adopt and defend beliefs that give us emotional and social benefits.

Emotional Benefits

Comfort

Helps us avoid unpleasant emotions, e.g. excruciating pain was an unavoidable (even divine) part of childbirth before we had epidural anesthesia, arguing that our mortality gives meaning to life.

Self-Esteem

Over time, our beliefs about the world adjust to accomodate our track record, e.g. poorer people are more likely to believe that luck plays a big role in life, while wealthier people tend to credit hard work and talent.

Morale

Especially when making tough decisions and acting on them with conviction, we selectively focus on the parts that justify optimism.

found that when employees held meetings to decide on a project to work on, they spent little time comparing options, and instead quickly anchored on one option and spent most of the meeting raising points in favor.

Social Benefits

Persuasion

To convince others of something, we become motivated to believe it ourselves, e.g. found that law students come to believe their side is both morally and legally in the right, even when the sides are randomly assigned.

Image

Some beliefs make us look a certain way, e.g. gravitating towards moderate positions on controversial issues in order to seem mature; looking for defensible rationalizations like being opposed to new construction for the impact on the environment, and not for wanting to keep owned property values high.

Belonging

Social groups hold beliefs and values that members are implicitly expected to share, e.g. all environmental policies are effective, children are a blessing, etc.

While deferring to consensus is often a wise heuristic because you don’t / can’t know everything, motivated reasoning occurs when you wouldn’t even want to find out if consensus was wrong.

Loyalty to a group biases members to be skeptical of evidence/arguments against the group. found strongly identified group members (e.g. gamers) publicly discrediting findings that threaten their social identity (e.g. effect of playing violent video games on aggression). Other research areas that are frequently battle grounds: anthropogenic climate change, evolutionary theory, side-effects of vaccines, effectiveness of alternative medicines, sexism, effects of unions on the economy, health effects of a vegetarian diet, etc.

quotes a gamer criticizing a YouTube video from a researcher on the effects of violent video games:

Another simple pseudo-scientist who gets a pat on the back for finding what he was looking for. No subtle thinking here. No qualifying or consideration of alternate interpretation. No honest presentation on the limitations of your study. No alternative explanations. This is why majority of social scientists are flimsy. It is a weak science desperately pretend it has hard evidence for complex phenomena.

Why Truth is More Valuable Than We Realize

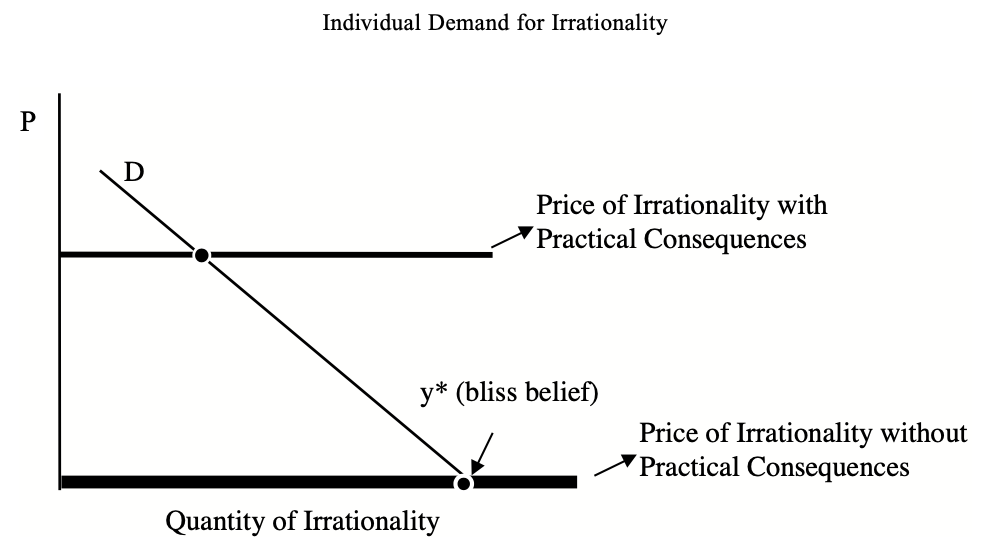

Epistemic rationality means holding beliefs that are well justified. Instrumental rationality means acting effectively to achieve your goals. ’s Rational Irrationality predicts that when private error costs are zero, agents will gather little information but form definite conclusions.

A key feature of beliefs is that some have practical consequences for the individual adherent. The question to ask is not, “What if everyone thought that way?” but rather “What would be different if I changed my mind?” If the answer is “nothing”, there is no marginal incentive to analyze the problem in an unbiased way.

Present bias makes us overvalue short-term consequences and under-value long-term ones, e.g. motivation to proceed vs. weighing alternatives.

We under-estimate the value of building scout habits, e.g. reasoning about something that doesn’t impact you directly still impacts you indirectly by reinforcing general habits of thought.

We under-estimate the ripple effects of self-deception, e.g. rosy self-perception makes it likely to dismiss people uninterested in you as shallow.

We overestimate how much other people judge us, and how much impact their judgments have on our lives.

The abundance of opportunity (e.g. kindred unconventional folks online or in a big city, choosing where to live, being able to cut ties with abusive family) makes the scout mindset far more useful to us than it would have been for our ancestors.

References

- The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don't. Chapter 1: Two Types of Thinking. Julia Galef. 2021. ISBN: 9780735217553 .

- How We Know What Isn't So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life. Thomas Gilovich. 1991. ISBN: 9780029117064 .

- The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don't. Chapter 2: What the Solider is Protecting. Julia Galef. 2021. ISBN: 9780735217553 .

- Chesterton's fence. en.wikipedia.org . wiki.lesswrong.com . Accessed Dec 17, 2021.

- The irrationality of action and action rationality: decisions, ideologies and organizational actions. Brunsson, Nils. Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1: 29 - 44. 1982.

- The Case for Mortality. Leon R. Kass. The American Scholar, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 173 - 191. www.jstor.org . 1983.

- Lifespan: Why We Age - and Why We Don't Have To. Sinclair, David. lifespanbook.com . Accessed Dec 18, 2021.

- Do Lawyers Really Believe Their Own Hype, and Should They? A Natural Experiment. Zev J. Eigen; Yair Listokin. The Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 239 – 267. doi.org . 2012.

- Social Identity Threat Motivates Science-Discrediting Online Comments. Nauroth, Peter; Gollwitzer, Mario; Bender, Jens; Rothmund, Tobias. PLoS One, Vol. 10, No. 2. doi.org . 2015.

- The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don't. Chapter 3: Why Truth is More Valuable Than We Realize. Julia Galef. 2021. ISBN: 9780735217553 .

- Rational Ignorance versus Rational Irrationality. Bryan Caplan. Kyklos, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 3 - 26. scholar.google.com . 2001.

Folks like approach ageing as a disease that we can cure.