Part I Description

The sea floor is getting steeper. Maybe the sleigh keys got carried this way?

A massive school of glowing lanternfish swims past. They must spawn quickly to reach such large numbers - maybe exponentially quickly? You should model their growth to be sure.

Although you know nothing about this specific species of lanternfish, you make some guesses about their attributes. Surely, each lanternfish creates a new lanternfish once every 7 days.

However, this process isn’t necessarily synchronized between every lanternfish - one lanternfish might have 2 days left until it creates another lanternfish, while another might have 4. So, you can model each fish as a single number that represents the number of days until it creates a new lanternfish.

Furthermore, you reason, a new lanternfish would surely need slightly longer before it’s capable of producing more lanternfish: two more days for its first cycle.

A lanternfish that creates a new fish resets its timer to 6 not 7 (because

0 is included as a valid timer value). The new lanternfish starts with an

internal time of 8 and does not start counting down until the next day.

Realizing what you’re trying to do, the submarine automatically produces a list of the ages of several hundred lanternfish (your puzzle input).

Find a way to simulate lanternfish. How many lanternfish would there be after 80 days?

Part I Solution

The input is of the form:

3,4,3,1,2

… so nothing special with parsing. Using [Int] should do just fine.

{-# LANGUAGE RecordWildCards #-}

{-# OPTIONS_GHC -Wall #-}

module AoC2021.Lanternfish (numOfFishIn80Days, numOfFishIn256Days) where

import Data.List (group, sort, foldl')

If the lanternfish’s internal timers were all in sync, then their population

on day \(d\) is of the form \(\lfloor n_0 \cdot r \cdot d \rfloor \), where

\(r\) factor of growth per day. Was unable to get a value for \(r\).

The case where \(n_0 = 1\), and the internal timer for the sole lanternfish

starts with a value of 0 should help determine \(r\). At the end of

\(d=1\), we’d have two lanternfish \([l_1, l_2]\) with internal timers of

6 and 8 respectively. At the end of \(d = 8\), \(l_1\) would produce

\(l_3\), and at the end of \(d = 10\), \(l_2\) will produce \(l_4\).

Enumerating the days when \(l_i\) produces a new \(l_j\):

$$ l_1 (d_{birth} = ?) \to 1, 8, 15, … $$ $$ l_2 (d_{birth} = 1) \to 10, 17, 24, … $$ $$ l_3 (d_{birth} = 8) \to 17, 24, 31, … $$ $$ l_4 (d_{birth} = 10) \to 19, 26, 33, … $$

Each case is an arithmetic series whose first term differs, but the difference

between consecutive terms is always 7. The number of fish at \(d\) is the

number of terms less than \(d\) in the expressions above, plus \(n_0\).

The sample input has starting internal timers of 3, 4, 3, 1, 2. Using the

notation above, and enumerating the individuals born at \(d \le 7\):

$$ l_4 (d_{birth} = ?) \to 2, 9, 16, … $$ $$ l_5 (d_{birth} = ?) \to 3, 10, 17, … $$ $$ l_1 (d_{birth} = ?) \to 4, 11, 18, … $$ $$ l_3 (d_{birth} = ?) \to 4, 11, 18, … $$ $$ l_2 (d_{birth} = ?) \to 5, 12, … $$ $$ l_6 (d_{birth} = 2) \to 11, 18, … $$ $$ l_7 (d_{birth} = 3) \to 12, 19, … $$ $$ l_8 (d_{birth} = 4) \to 13, 20, … $$ $$ l_9 (d_{birth} = 4) \to 13, 20, … $$ $$ l_{10} (d_{birth} = 5) \to 14, 21, … $$

… the sum of individuals is \(5 + 5 = 10\). I’m not sure how to turn this into an algorithm that doesn’t enumerate all individuals at day \(d\), and then computes the individuals at \(d+1\), and so forth until we get to \(d=80\).

Given an individual \(l_i\), we can compute the number of direct children the individual will have by \(d = 80\). However, we need to do this recursively as the children will also have children.

_numOfDirectChildren :: [Int] -> Int -> Int

_numOfDirectChildren (deliveryDay : deliveryDays) finalDay =

let

childrenBirthdays = [deliveryDay, deliveryDay + 7 .. finalDay]

childrenDeliveryDays = map (+9) childrenBirthdays

in length childrenBirthdays + _numOfDirectChildren

(deliveryDays ++ childrenDeliveryDays) finalDay

_numOfDirectChildren [] _ = 0

_numOfFishIn80Days' :: [Int] -> Int

_numOfFishIn80Days' internalTimers =

let deliveryDays = map (+1) internalTimers

in length internalTimers + _numOfDirectChildren deliveryDays 80

Debugging a recursive function using breakpoints is tedious. mentions the Hood package which can print all

invocations of a function f and their results. However, cabal install hood

fails because FPretty (dependency of Hood) requires base>=4.5 && <4.11,

while I have base==4.14.3.0 installed. I don’t want to demote by base.

_numOfFishIn80Days' is performant enough for the sample input that has 5

initial lanternfish being simulated for 80 days, but it chokes on part I, whose

input has 300 initial lanternfish over the same period of time.

Let’s try a more straightforward (but less efficient?) approach, where we track

individuals in [Int].

simulateFishGrowth :: [Int] -> [Int] -> [Int]

simulateFishGrowth (_:days) internalTimers =

let nextUnadjustedTimers = map (\t -> t - 1) internalTimers

numChildren = length $ filter (< 0) nextUnadjustedTimers

adjustedTimers = map (\v -> if v < 0 then 6 else v) nextUnadjustedTimers

in simulateFishGrowth days (adjustedTimers ++ replicate numChildren 8)

simulateFishGrowth [] internalTimers = internalTimers

numOfFishIn80Days :: [Int] -> Int

numOfFishIn80Days = length . simulateFishGrowth [1 .. 80]

I thought _numOfDirectChildren was more efficient than simulateFishGrowth,

but turns out that the latter handles 300 initial lanternfish over a period of

80 days, while the former chokes. The answer of the final simulateFishGrowth

call is the answer of the whole problem, so maybe the compiler did some tail

recursion optimization?

’s naïve solution is more elegant:

rules :: Int -> [Int]

rules clock

| clock == 0 = [8, 6]

| otherwise = [clock - 1]

step :: [Int] -> [Int]

step = (>>= rules)

iterate :: Int -> (a -> a) -> a -> [a]

iterate n f x

| n == 0 = [x]

| otherwise = x : iterate (n - 1) f (f x)

numOfFishIn80Days :: [Int] -> Int

numOfFishIn80Days = length . last . iterate 80 step

The use of the bind operator in the step function is foreign to me,

as I’ve

only interacted with the (>>=) operator in monadic contexts

. How do we go from as >>= bs as syntactic sugar for do a <- as, bs a

to it being used form an [Int] -> [Int] from an Int -> [Int]? Maybe the two

are not related? Ah, :type (>>=) is Monad m => m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b,

and the list is a monad. So in this case, we have

[Int] -> (Int -> [Int]) -> [Int], where rules satisfies the (Int -> [Int])

part. Huh, the more you see monads, the more it starts clicking.

I also have an anti-pattern in simulateFishGrowth, where I take [1, 2 .. 80]

instead of taking 80 as an input. I could have then pattern-matched as

did in the iterate function.

Part II Description

Expected extension for Part II: accounting for the fact that lanternfish die after some time. A lanternfish does not keep reproducing indefinitely.

Update: Wrong guess. Death wouldn’t complicate simulateFishGrowth too much.

the major change would be instead of tracking only the internal timers, we’d

track the age of the lanternfish. Increasing the number of days being simulated

makes a naïve solution contend with an exponential blowup.

Suppose the lanternfish live forever and have unlimited food and space. Would they take over the entire ocean?

After 256 days in the example above, there would be a total of 26,984,457,539 lanternfish!

How many lanternfish would there be after 256 days?

Part II Solution

Simulating 256 days will cripple simulateFishGrowth. In the sample input,

we’ll have a list with 27B items, up from 6k items! If the the same explosion is

applied to the puzzle input, we’re expecting a final list with

\(360{,}610 \cdot (26{,}984{,}457{,}539 / 5{,}934) \approx

1{,}639{,}849{,}213{,}538 \) items. Under the rosiest projections, each entry

in the [Int] takes 8 bytes, we need

\(\ge 1{,}639{,}849{,}213{,}538 \cdot 8 / 1{,}024^4 \approx 11.93 \text{TB}\).

That’s beyond my laptop’s range.

-- Takes too long

_numOfFishIn256Days' :: [Int] -> Int

_numOfFishIn256Days' = length . simulateFishGrowth [1 .. 256]

One more attempt before looking up how to model unbounded population growth. There exists some cohort of lanternfish that are giving birth on the same day. If we have a lanternfish that reproduces on \(d = [0, 7, 14, …]\), the second generation will reproduce on \(d = [9, 16, …]\), the third on \(d = [16, 23, …]\), the fourth on \(d = [23, 30, 37, …]\), and so forth. Hmm… I don’t see it. Time to consult population growth literature.

The term for the kind of growth exhibited by the lanternfish is exponential growth, because each lanternfish gives forth one lanternfish. Exponential growth is described by \(x_t = x_0 \cdot b^{t/\tau}\), where \(b\) is a positive growth factor, and \(\tau\) is the time required for \(x\) to grow by one factor of \(b\). The simple case where each lanternfish creates a new one every seven days and is in sync with every other lanternfish, can be modelled by \(x_t = x_0 \cdot 2^{t/7}\). I still don’t see a way of adapting \(x_t = x_0 \cdot b^{t/\tau}\) to account for the out of phase internal timers, and the initial \(\tau = 7\).

What about maintaining a list of InternalTimer {t :: Int, count :: Int}. This

list will have at most 9 items because t can only assume values in

\([0,1,…8]\). Then on each day, we can update this list. The memory blow-up

experienced earlier is avoided by collapsing all of the n items of value t

in the original [Int] into a single InternalTimer{t = t, count = n}.

Now that I type the above out, why didn’t it hit me sooner? has a section on “Exponential Growth Bias”, the tendency to underestimate compound growth processes, e.g. a king was gifted a chess board, and agreed to re-gifting the donor with one grain of rice for the first square, two grains for the second square, four grains for the third square, and so forth; however, the \(2^{n-1}\) grains ballooned up pretty quick (e.g. \(2^{40} = 1{,}099{,}511{,}627{,}776\)), that it was infeasible to provide them. I wouldn’t go as far as to say, “Since we have an exponential growth process, to simulate this naively would be stupid, which is kind of the point of the exercise,” as that is hostile to someone realizing that they have fallen to the exponential growth bias.

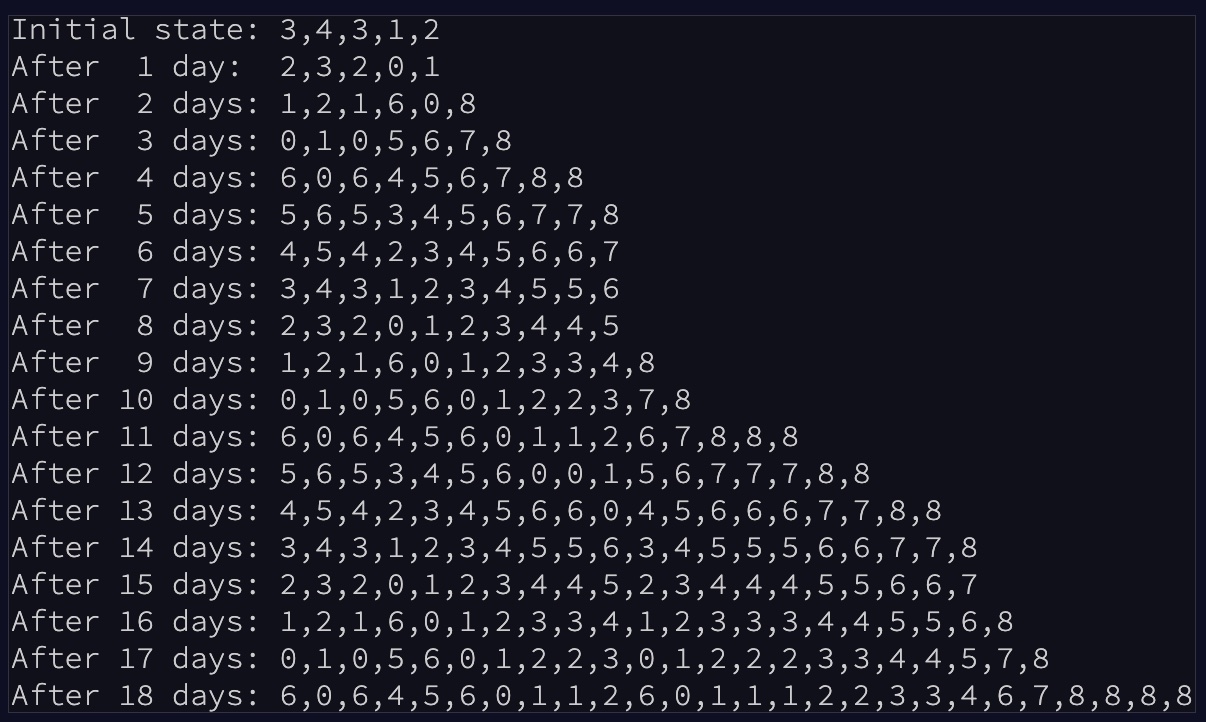

I’ve heard the parable of the chess board and the rice, but it didn’t really hit me that I was the king. When I looked at this sample simulation for the test input, the growth didn’t seem all that fast; we add a couple of 8’s every so often, piece of cake. This problem was a good wake-up call to not be smug about never being on the receiving side of a bias that I already know! Image taken from https://adventofcode.com/2021/day/6.

data InternalTimers = InternalTimers {

t0 :: Integer, t1 :: Integer, t2 :: Integer, t3 :: Integer, t4 :: Integer,

t5 :: Integer, t6 :: Integer, t7 :: Integer, t8 :: Integer} deriving Show

-- TODO: How do I avoid passing a phantom int to advanceInternalTimersOneStep?

-- I just wanted to call `advanceInternalTimersOneStep` 256 times in a fold

-- statement...

--

-- Answer: instead of using fold, write a recursive

-- `advanceInternalTimersNSteps :: Int -> InternalTimers -> InternalTimers`, and

-- do `finalTimers = advanceInternalTimersNSteps 256 internalTimers`

advanceInternalTimersOneStep :: InternalTimers -> Int -> InternalTimers

advanceInternalTimersOneStep InternalTimers{ .. } _ =

let originalT0 = t0

in InternalTimers{t0 = t1, t1 = t2, t2 = t3, t3 = t4, t4 = t5, t5 = t6,

t6 = t7 + originalT0, t7 = t8, t8 = originalT0}

InternalTimers could have also been a Data.Map Int Integer. The named field

has some awkward bits, e.g. the need to pad the [Integer] in

extractCohortCounts and in internalTimersFromRawData.

A sample implementation of advanceInternalTimersNSteps:

advanceInternalTimersNSteps :: Int -> InternalTimers -> InternalTimers

advanceInternalTimersNSteps n internalTimers@InternalTimers{ .. }

| n == 0 = internalTimers

| otherwise =

let originalT0 = t0

currTimers = InternalTimers{t0 = t1, t1 = t2, t2 = t3, t3 = t4,

t4 = t5, t5 = t6, t6 = t7 + originalT0,

t7 = t8, t8 = originalT0}

in advanceInternalTimersNSteps (n - 1) currTimers

The t0 = t1, t1 = t2, ... could make use of a circular data structure, so

that we’re only moving the “head”, and not the data itself. But given that

Haskell values are immutable, we don’t have much to gain (and potentially more

to lose as we add the complexity of implementing circular data structure and

locating a given cohort).

numPossibleInternalTimers :: Int

numPossibleInternalTimers = 9 -- [0, 1, 2, ..., 8]

extractCohortCounts :: [[Int]] -> [Integer]

extractCohortCounts (l:ls) =

let currentCohort = head l

-- TODO: Is there a common idiom for this. I repeat it in

-- `internalTimersFromRawData` too...

numFillers = if null ls && currentCohort > 0

then currentCohort

else currentCohort - head (head ls) - 1

cohortCountEntries = toInteger (length l) : replicate numFillers (0 :: Integer)

in cohortCountEntries ++ extractCohortCounts ls

extractCohortCounts [] = []

internalTimersFromRawData :: [Int] -> InternalTimers

internalTimersFromRawData ts =

let

reversedGrouping = group $ reverse $ sort ts

possiblyPartialCohorts = extractCohortCounts reversedGrouping

frontPaddingSize = if null reversedGrouping

then numPossibleInternalTimers

else numPossibleInternalTimers - head (head reversedGrouping) - 1

extractedCohortCounts = reverse possiblyPartialCohorts ++

replicate frontPaddingSize 0

-- TODO: Link to StackOverflow answer with suggestion.

internalTimers = InternalTimers{..} where

[t0, t1, t2, t3, t4, t5, t6, t7, t8] = extractedCohortCounts

in internalTimers

numOfFishIn256Days :: [Int] -> Integer

numOfFishIn256Days rawTimers =

let

days = [1, 2 .. 256]

internalTimers = internalTimersFromRawData rawTimers

finalTimers = foldl' advanceInternalTimersOneStep internalTimers days

totalPopulation = t0 finalTimers + t1 finalTimers + t2 finalTimers

+ t3 finalTimers + t4 finalTimers + t5 finalTimers

+ t6 finalTimers + t7 finalTimers + t8 finalTimers

in totalPopulation

References

- Debugging - HaskellWiki. wiki.haskell.org . Accessed Mar 2, 2022.

- Exponential Growth - Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org . Accessed Mar 4, 2022.

- Advent of Code 2021 : Day 06. Lanternfish. jhidding.github.io . Accessed Mar 5, 2022.

There should be some established literature on population growth modeling. For example, ORF 309 covered the Galton-Watson process, which is basically this question, with the descendants being born with some probability, and everyone in sync.

I wonder how close I’ll get from reasoning my way through.