The term “consistent hashing” makes me think of hashing without randomization. Why isn’t every hash consistent by definition? For example, a map implementation would need consistent hashing lest it’s inaccurate when searching for stored values. Or is consistent hashing a tradeoff between collision-resistance and speed?

Web Caching

Web caching was the original motivation for consistent hashing. With a web cache, if a browser requests a URL that is not in the cache, the page is downloaded from the server, and the result is sent to both the browser and the cache. On a second request, the page is served from the cache without contacting the server.

Web caching improves the end user’s response time. It also reduces network traffic overall.

While giving each user their own cache is good, one could go further and implement a web cache that is shared by many users, e.g., all users on a campus network. These users will enjoy many more cache hits.

Akamai’s goal was to turn a shared cache into a viable technology. Their claim

to fame was in March 31, 1999. Apple was the exclusive distributor for the

trailer for “Star Wars: The Phantom Menace”. apple.com went down almost

immediately, and for a good part of the day, the only place to watch the trailer

was via Akamai’s web caches.

Caching pages for a large number of users needs more storage than is available

on one machine. Suppose the shared cache is spread over \(N\) machines; where

should we look for a cached copy of www.contoso.com?

Simple Solution Using Hashing

A hash function, \(h\), maps elements of a large universe \(U\) to “buckets”, e.g., mapping URLs to 32-bit values. A good \(h\):

- Is easy to compute, e.g., a few arithmetic operations and maybe a mod.

- Behaves like a totally random function, spreading out data evenly without notable correlations across the possible buckets.

Designing good hash functions isn’t easy, but can be treated like a solved problem. In practice, it’s common to use the MD5 hash function.

Suppose we have \(n\) caches named \({0, 1, 2, …, n-1}\). Let’s store the web page with URL \(x\) at the cache server named \(h(x) \mod{n}\).

In practice, \(n\) is not fixed, e.g., web caches can be added or removed due to business or network conditions. With the aforementioned approach, changing \(n\) forces almost all objects to relocate. Moving data between machines across a network is expensive, especially when \(n\) is prone to change.

Compare this to hash table implementations. When the load factor (no. of elements divided by no. of buckets) increases, search time degrades, and hash table implementations increase the number of buckets and rehash everything. While rehashing is an expensive operation, it’s invoked infrequently and the data is moved within the same machine.

Consistent Hashing

The goal of consistent hashing is to provide hash table-type functionality and have almost all objects stay assigned to the same cache even as the number \(n\) of caches changes.

There are several implementations of consistent hashing, but here’s one:

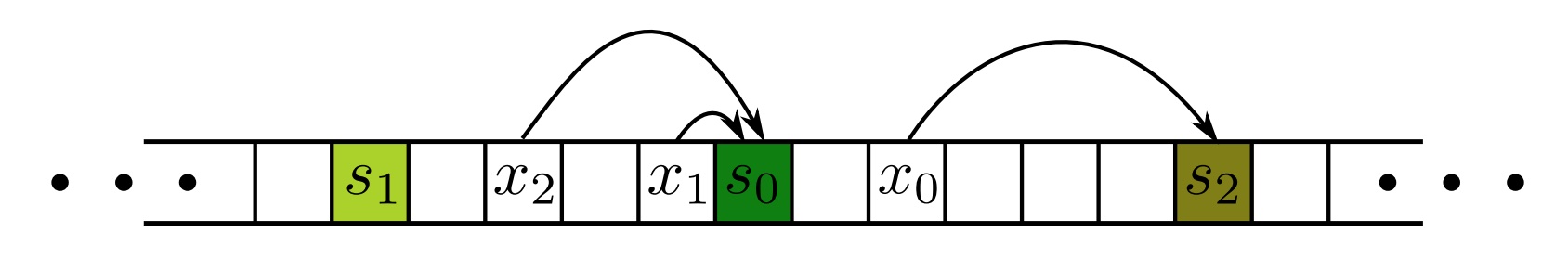

- Hash the names of all cache servers, i.e., \(h(s)\), and note them in the corresponding buckets.

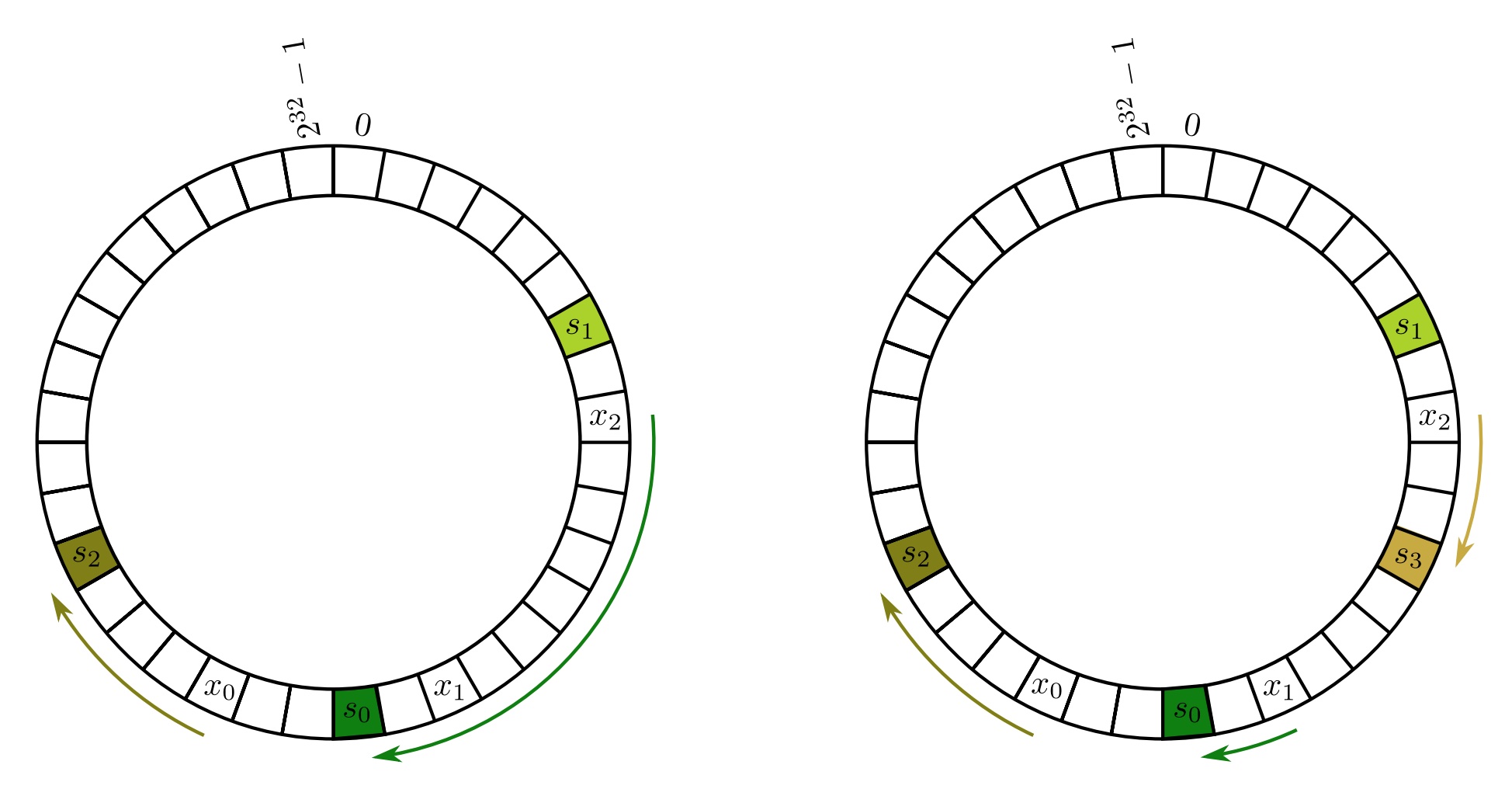

- Given an object \(x\) that hashes to the bucket \(h(x)\), scan buckets to the right of \(h(x)\) until we find a bucket \(h(s)\). Wrap around the array if need be.

- Designate \(s\) as the cache responsible for the object \(x\).

Each element of the array is a bucket of the hash table. Each object x is assigned to the first cache server s on its right. Credits: https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs168/l/l1.pdf

Left: wrapping the two ends of the array solves the problem of an object x being to the right of the last cache. Right: adding a new server s3 only requires that x2 be moved from s0 to s3. Credits: https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs168/l/l1.pdf

Assuming a uniform \(h\), the expected load on each of the \(n\) cache servers is \(\frac{1}{n}\) of the objects. When we add a new cache server \(s\), only the objects stored at \(s\), roughly \(\frac{1}{n}\) objects, need to relocate. This is much better than the naive solution where \(\frac{n-1}{n}\) of the objects are expected to relocate when the \(n\)-th cache is added!

How do objects get moved? The new cache server could identify its “successor” and send a request for the objects that hash to the relevant range. However, in a web cache context, there is no need to do anything. New requests will miss the object in the new cache and force it to be downloaded and cached. The old cache in the “successor” node will eventually time out and be deleted.

The lookup and insert hash table operations need an efficient

rightward/clockwise scan operation. Hash tables don’t work because they don’t

maintain ordering information. A heap only maintains a partial order so that

finding the minimum is fast. A binary tree maintains total order, and exposes a

successor operation. For a balanced binary tree, the successor operation

takes \(\mathcal{O}(log(n))\) time, where \(n\) is the number of caches.

Third-generation peer-to-peer (P2P) networks use consistent hashing to keep

track of where everything is. However, nobody is keeping track of the full set

of cache servers. How can successor be implemented? The high-level idea is

that each machine is responsible for keeping track of a small number of machines

in the network. An object search is then sent to the appropriate machine using a

clever routing protocol.

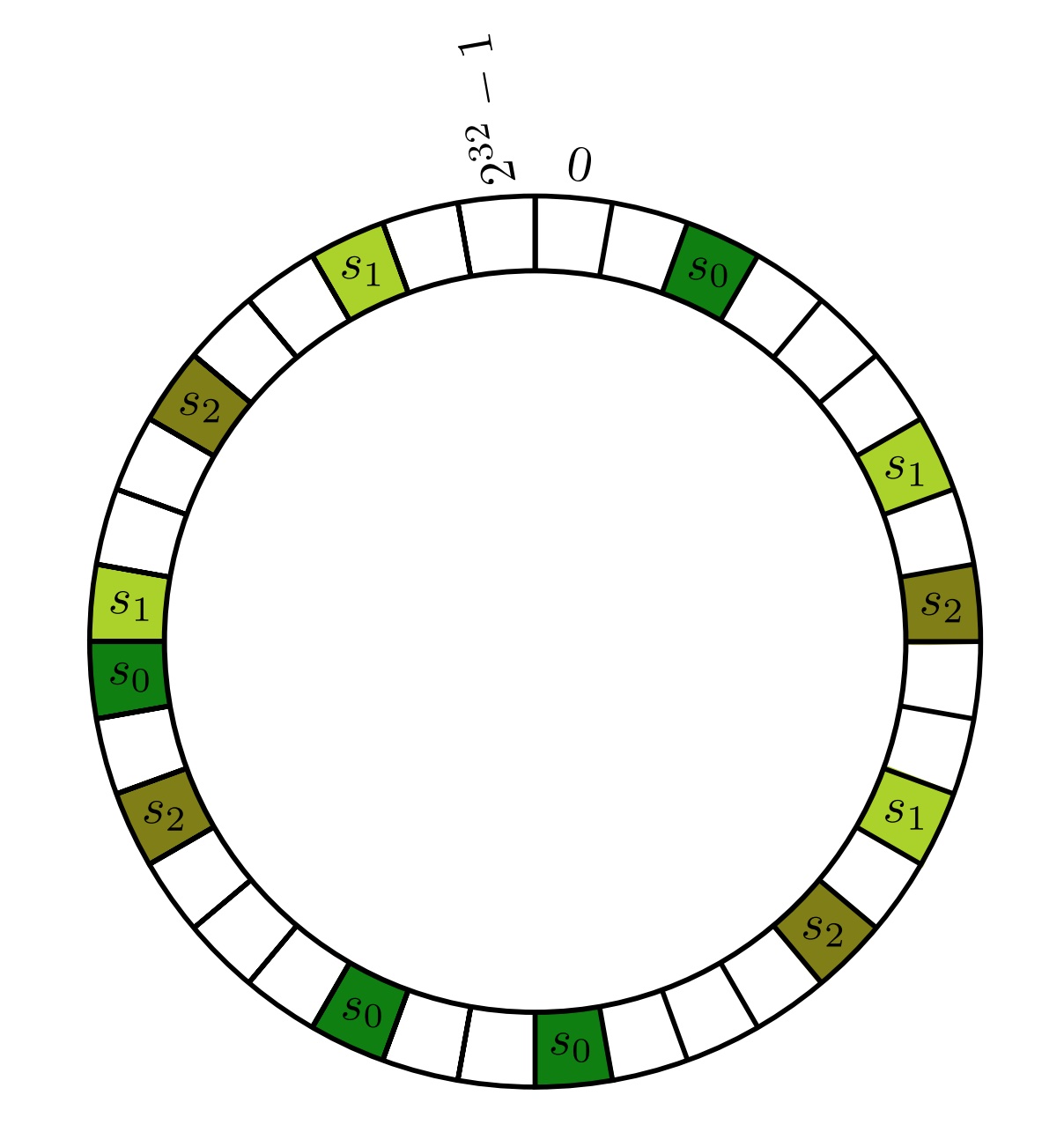

While the expected load of each cache server is \(\frac{1}{n}\) of the objects, the realized load of each cache server will vary. One way to decrease this variance is to hash each server, \(s\), with \(k\) different hash functions to get \(h_1(s), …, h_k(s)\). Objects are assigned as before, i.e., scan clockwise until we encounter one of the hash values of some cache \(s\), and \(s\) is responsible for storing \(x\). By symmetry, each cache still expects a load of \(\frac{1}{n}\), but the variances in load across cache servers is reduced significantly. Choosing \(k \approx log_{2}n\) is large enough to obtain reasonably balanced loads.

Decreasing the variance by assigning each cache server multiple hash values. Credits: https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs168/l/l1.pdf

References

- CS168: The Modern Algorithmic Toolbox. Lecture #1: Introduction and Consistent Hashing. Tim Roughgarden; Gregory Valiant. web.stanford.edu . Apr 2, 2024.

- ACM STOC Conference: The ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. acm-stoc.org . Accessed Nov 27, 2025.

Web caching can sometimes get in the way. For example, when designing a blog with comments , if a blog post gets a new comment, then the caches of that blog post need to get busted so that the updated post is served.